The Mutant Advantage

If you grew up watching Saturday morning cartoons or flipping through dog-eared X-Men comics, you know Professor Xavier. The bald telepath in the wheelchair, leader of the mutant superhero team, blessed with the ability to read minds and project his thoughts across vast distances.

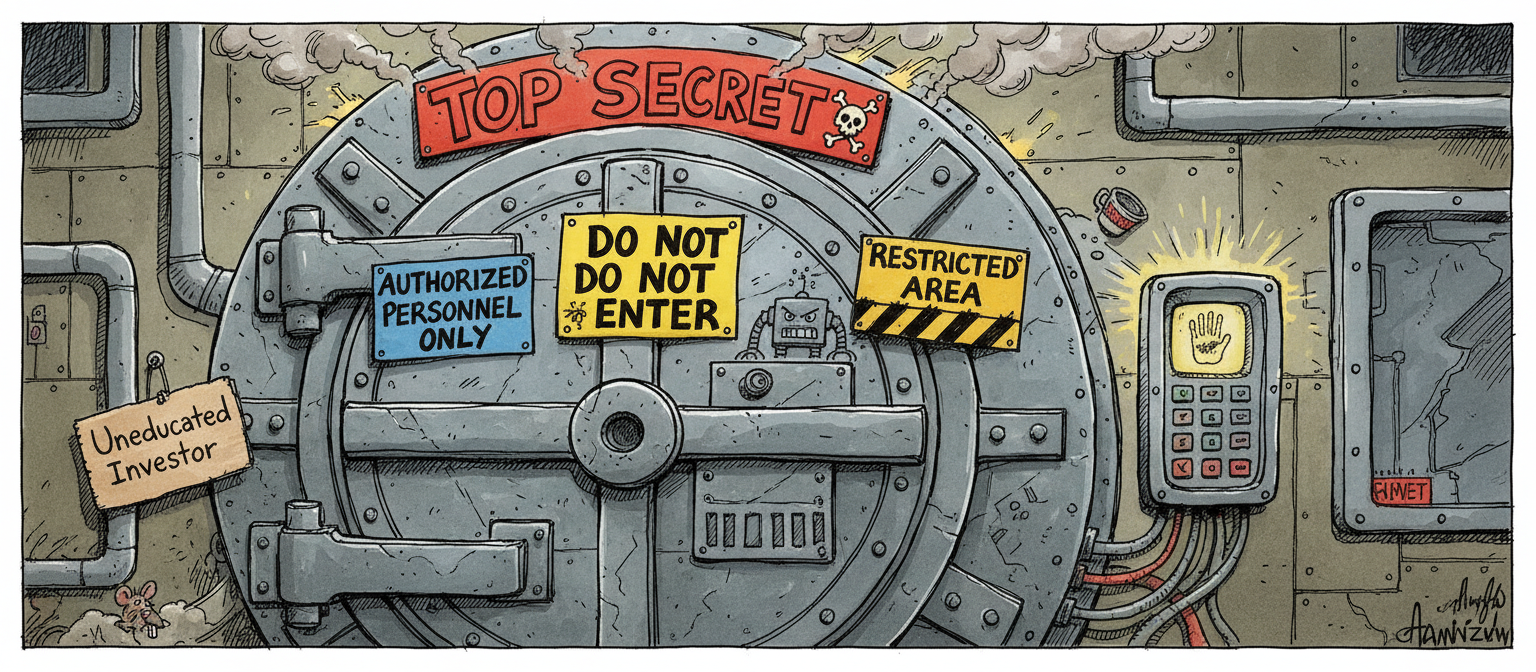

But Professor Xavier had a secret weapon that made him even more powerful: Cerebro.

Cerebro was a device that amplified Xavier’s already formidable psychic abilities, allowing him to detect mutants anywhere on Earth and read the collective consciousness of humanity. Where Xavier’s natural powers had limits, Cerebro removed them. He could process signals he’d otherwise miss. See patterns invisible to the unaided mind. Find needles in haystacks the size of continents.

Now ask yourself this:

What if you had a Cerebro for markets?

Not to find mutants hiding among humans, but to find alpha hiding in global news flow. Not to read minds, but to read the second-order consequences that everyone else ignores.

The Trade Wall Street Missed

Late November 2025. Google drops Gemini 3, its latest AI model, and the tech world collectively loses its mind. Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff declares he’s abandoning ChatGPT after using it religiously for three years. “The leap is insane,” he posts. “Everything is sharper and faster.”

The obvious trade? Buy Google. And sure enough, Alphabet stock surged—up 70% for the year, adding hundreds of billions in market cap.

But here’s what most investors missed: Google didn’t train Gemini 3 on Nvidia chips. They built it entirely on their own TPUs—Tensor Processing Units designed in-house specifically for AI workloads. For the first time in nearly a decade, stocks leveraged to Google’s chip ecosystem started trading at a premium to those tied to Nvidia’s GPUs.

The first-order thinkers bought Google and called it a day.

The second-order thinkers asked: “Wait, who manufactures Google’s TPUs?” The answer: Broadcom. And while everyone was busy congratulating themselves for buying the obvious winner, Broadcom quietly joined the “Google Complex” of outperformers.

Then came the kicker—reports that Meta was exploring a multi-billion dollar deal to use Google’s TPU capacity in their data centers. Nvidia’s stock dropped 5% in a day. They posted a defensive message on X insisting they were still “a generation ahead.” When you’re the undisputed champion and suddenly you’re posting defensive threads on social media, the regime is shifting.

The really sophisticated thinkers went even deeper: Who supplies the advanced packaging for Broadcom’s chips? Where’s the CoWoS capacity constraint? Who has pricing power three steps removed from the headline?

That’s not first-order thinking. That’s not even second-order. That’s playing chess while everyone else is playing checkers.

Why Wall Street Is Structurally Blind

Every analyst on the Street can execute first-order thinking. Russia invades Ukraine → defense stocks rise. Coffee crops fail → coffee prices increase. It’s simple cause and effect, and the market prices it in before you finish reading the headline.

The problem is that the really interesting opportunities—the ones that generate actual alpha—live in the second and third order effects. The cascading consequences that take weeks or months to materialize. The structural shifts that change who wins and who loses in ways the initial headline doesn’t reveal.

But institutional investors are terrible at this, and it’s not because they’re stupid. It’s because they’re constrained.

Quarterly thinking dominates. If a thesis takes six months to play out, it might as well not exist. Career risk compounds the problem—you get fired for being early just as quickly as you get fired for being wrong. Herd behavior provides safety; if everyone misses the trade, no one gets blamed. And the sheer volume of information flowing through markets every day overwhelms human processing capacity. You can’t read everything, think through every implication, stress-test every assumption, and still make it home for dinner.

The real edge isn’t in having better information. It’s in processing the information everyone already has in a way that surfaces what they’re missing.

The Pattern Hidden in Plain Sight

Let’s look at two examples that show how second-order thinking actually works.

Example 1: The Coffee Trade

Coffee plantations across multiple regions start reporting crop failures—weather damage, disease, the usual culprits of agricultural disruption. First-order thinking says: Coffee supply decreases → coffee prices rise. Fine. Obvious. Completely priced in within 24 hours.

But the second-order insight asks a different question: What happens to demand?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about coffee: people don’t quit. They don’t switch to tea. They don’t skip their morning ritual because their latte went from $4.50 to $6.00. Consumer demand for coffee is remarkably inelastic—it’s borderline addiction dressed up as a morning routine. Which means when supply contracts and demand holds steady, you don’t get a temporary price spike. You get a sustained structural shift in pricing with persistent demand.

That’s not just “coffee prices go up.” That’s a different thesis entirely—one that changes the risk-reward on a 6-month or 12-month horizon.

Example 2: The European Defense Awakening

February 2022. Russia invades Ukraine. Every trader on the planet immediately bought U.S. defense contractors—Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman. The first-order trade was so obvious it might as well have been written in neon.

But the second-order observers asked: “What happens to Europe?”

For decades, European nations had outsourced their security to NATO and let their defense budgets atrophy. Germany was spending barely 1% of GDP on defense. France’s military was a shadow of its Cold War self. The entire continent had been living in a geopolitical fantasy land where threats didn’t exist and America would always pick up the check.

Russia’s invasion shattered that illusion. Overnight, defense spending became politically viable—necessary, even. Germany announced a €100 billion special defense fund. Poland started shopping for tanks. Sweden and Finland joined NATO and began modernizing their militaries.

The second-order trade was seeing the shift in the European zeitgeist. It was European defense companies that had been starved of investment for 30 years and were suddenly facing a structural demand shift that would last a decade.

Most investors bought the obvious first-order play and missed the structural second-order opportunity entirely.

The Brutal Math of Human Limitations

The challenge isn’t intellectual—it’s mechanical. You need to process massive amounts of global information continuously. Separate structural changes from routine noise. Build logic chains that account for cascading effects and unintended consequences. Validate assumptions through skeptical review rather than confirmation bias. And connect abstract insights to actual tradeable opportunities.

Now do that systematically, at scale, without the career risk and quarterly pressure that make institutional investors herd animals.

A human analyst working 80-hour weeks might identify one or two of these opportunities per quarter if they’re exceptionally talented. But systematic identification across global markets, delivered consistently? That’s a different game entirely.

The result wouldn’t be more ideas. It would be fewer, better ideas. Two or three actionable theses per week, each with a clear logic chain from catalyst to trade, delivered before the narrative becomes consensus.

You wouldn’t be competing on speed—that’s an arms race you’ll lose to high-frequency traders. You’d be competing on depth. On seeing patterns that sophisticated investors eventually recognize, but reaching the conclusion three months earlier.

The edge wouldn’t be predicting the future. The edge would be seeing how the present is shifting before Wall Street’s models catch up.

The Question

Traditional finance still runs on analysts reviewing quarterly earnings, mining credit card data for consumer spending signals, and attending management presentations where CFOs read from pre-approved scripts. It’s humans processing information at human speed, constrained by human cognitive limits and human institutional pressures.

But we don’t live in a traditional finance world anymore. We live in a world where processing power is abundant, where machines can evaluate scenarios without fatigue or bias, where systematic thinking can operate at scale in ways human analysts cannot.

The mandate for a system like this—a Cerebro for markets—is obvious: identify second and third-order opportunities before they become consensus trades.

So here’s my question: If such a system could be built, what would it be worth? How much could one make by being able to see the cascading consequences that others miss? What’s the edge worth when you’re positioned in Broadcom while everyone else is still congratulating themselves for buying Google?

And the more interesting question: If a system like this could exist—if the architecture is feasible and the value proposition is clear—then why isn’t somebody already building it?

Or is somebody building it now?